Table of Contents

- Adjective Endings

- Personal Pronoun + Verb: Contractions

- Numbers

-

Unit 5 Review

- Articles and Adjective Endings

- The Definite Article: Accented and Unaccented

- The General Pronoun דאָס/דעם

- טאַטן, זײדן, מאַמען, באָבען

- The Reflexive Pronoun זיך

- נישטאָ

- The Past Tense

- Directional Converbs: When the Base Form of the Verb is Absent

- (צו) + Infinitive

- The Position Verbs לײגן, ליגן, זעצן, זיצן, שטעלן, שטײן

- Word Order in a Declarative Sentence Without Special Emphasis

- Word Order in Compound Sentences

Adjective Endings

When does an adjective have an ending?

Up until now, we have only encountered the short form of adjectives in YiddishPOP, for example װײַס and פֿרײלעך in sentences 1 and 3 above. Most adjectives also have long forms that consist of the short form with an ending. When an ending is added, we say that the adjective declines. The long forms are used when the adjective comes right before the noun, for example װײַסע and פֿרײלעכע in sentences 2 and 4.

What endings do adjectives have?

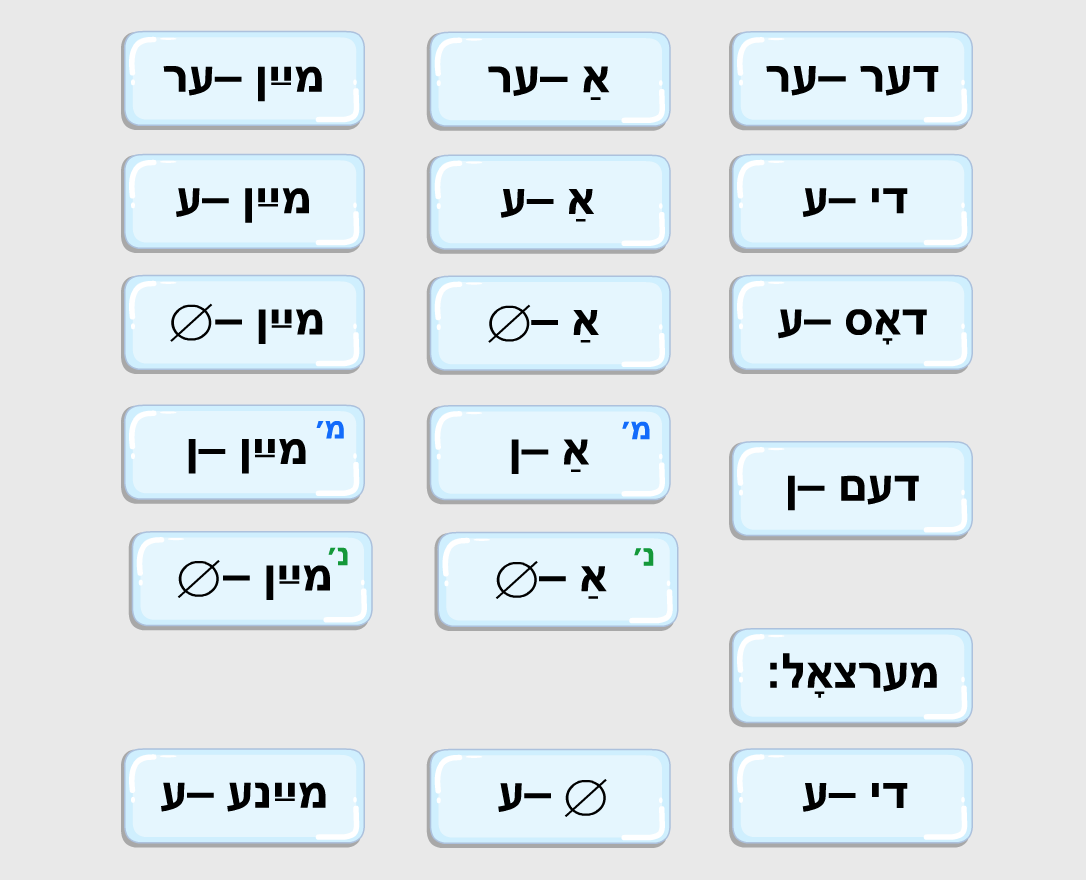

Like the definite article, an adjective changes according to the gender, number, and case of the noun with which it is associated. The definite article can serve as a guide to these changes because each form of the definite article comes with a particular ending:

It makes no difference, for example, whether דער is masculine nominative or feminine dative, this article always comes with the ending ער–:

- דער רױטער מאַנטל הענגט לעבן דער בלאָער שאַל.

דעם always comes with the ending ן–; in the following sentence, the first דעם is masculine accusative and the second דעם is neutral dative:

- איך טראָג דעם רױטן מאַנטל מיטן (= מיט דעם) געלן היטל.

די comes with the ending ע–. The pair די –ע is not only feminine nominative and feminine accusative in the singular, but also plural for all genders and cases. For example:

- איך טראָג די בלאָע שאַל און דו טראָגסט די שװאַרצע שיך.

- די גוטע חבֿרים קוקן אױף די אַלטע בילדער.

Even when the definite article is not present, an adjective has the same endings according to gender, number, and case (with one important exception, see below on the “null ending”). Compare the following sentences with the definite article, the indefinite article, the negative article קײן, the possessive pronoun, and where there is no article:

- דער רױטער מאַנטל הענגט לעבן דער בלאָער שאַל.

- אַ רױטער מאַנטל הענגט לעבן אַ בלאָער שאַל.

- מײַן רױטער מאַנטל הענגט לעבן דײַן בלאָער שאַל.

- קײן רױטער מאַנטל הענגט נישט לעבן קײן בלאָער שאַל.

- ער טראָגט דעם רױטן מאַנטל מיט די שװאַרצע שיך.

- ער טראָגט אַ רױטן מאַנטל מיט שװאַרצע שיך.

- ער טראָגט זײַן רױטן מאַנטל מיט מײַנע שװאַרצע שיך.

- ער טראָגט נישט קײן רױטן מאַנטל און אױך נישט קײן שװאַרצע שיך.

Variants of the Ending ן–

- ער טראָגט אַ בלאָען מאַנטל מיט אַ גרינעם שירעם.

The ending ן– is sometimes pronounced, and therefore also spelled, ען– or עם–. This depends on the sound with which the adjective ends, as explained in the following table:

The Null Ending

An adjective has the null ending when:

For example:

- דאָס גרינע העמד הענגט לעבן דעם געלן העמד.

- אַ גרין העמד הענגט לעבן אַ געל העמד.

- מײַן גרין העמד הענגט לעבן דײַן געל העמד.

- קײן גרין העמד הענגט נישט לעבן קײן געל העמד.

- איך האָב אײן גרין העמד און צװײ געלע העמדער.

- װעמענס גרין העמד הענגט לעבן דײַן געל העמד?

- אַזאַ שמוציק העמד קען איך נישט טראָגן.

Note:

Adverbs

The short form of very many adjectives can also serve as an adverb. For example:

There follow several sentences from YiddishPOP movies with adjectives in their short form serving as adverbs:

- שטײט גלײַך, שטעקלעך! שטײט נישט קרום! (2.5)

- אױ, פּינטל, דו קענסט נישט כאַפּן, דו קענסט נישט ברענגען – אָבער דו קענסט גוט שלאָפֿן! (3.1)

- די הײמאַרבעט איז: „קוק גוט אָן אַ חיה, און שרײַב װעגן איר“. (5.1)

- װען איך האָב דיך נישט לאַנג געזען, ביסטו דאָך געװען געזונט און שטאַרק. (5.3)

- נאָך דעם איז מיר װײַטער געגנאַנגען אַזױ שרעקלעך. (5.4)

- אָבער דאָס קלײד איז מיר אַזױ שטאַרק געפֿעלן! (5.5)

There are also adverbs that are not the same as the short form of an adjective. Here are several that we have learned in YiddishPOP:

Summary

The following tables summarize the articles and adjective endings in two ways:

A. By article (summary taken from the grammar movie):

B. By gender, case and number:

A summary of the adjective endings can be printed/downloaded here: אַדיעקטיװ־ענדונגען.

Personal Pronoun + Verb: Contractions

1. The Personal Pronoun Contracts

- װוּ הענגט דאָס בילד? ס׳הענגט אין דער סוכּה.

- װאָס טרינקסטו? כ׳טרינק אַ גלעזל טײ.

- דער טאַטע איז דאָ? נײן, ר׳איז אַרױס.

Some personal pronouns sometimes contract before the verb. The following contractions of עס and איך may be used with many different verbs:

The contraction of ער occurs mainly with איז and האָט:

The following table provides further examples with the contracted forms of איך, עס and ער:

These contractions are very natural in spoken Yiddish and are also common in writing.

Note:

2. The Helping Verb Contracts

The helping verbs for the future and past tenses (װעל and האָבן) sometimes contract, usually after the subject pronoun. With some pronouns, the contraction is the same for both helping verbs as can be seen in the table below. A contraction with the helping verb װעל comes, of course, with an infinitive; a contraction with the helping verb האָבן – with a participle.

Contracted helping verbs are more common in speech than in writing.

Numbers

1–99

The way the numbers are listed in the following table emphasizes the patterns:

- number + צן

- number + ציק

for example:

This pattern applies to all numbers from 3 to 9, but with variations, as can be seen in the table.

*On אײן vs. אײנס, see 1.3 נאָך פּרטים.

Order of Tens and Ones

In the numbers 21 to 99, the ones come before the tens, and they are joined with the word און.

Higher Numbers

Although we only learn to count to 100 in the grammar movie, we provide here a guide to higher numbers.

Here are some examples of numbers greater than 100. Note that within these larger numbers, 21 – 99 are always “reversed” (the ones before the tens). For example:

אַ with a Number

הונדערט and טױזנט come without the words אײן or אַ:

The word אַ with a number means approximately. For example:

This does not, however, apply to אַ מיליאָן where אַ means “one” (and not “approximately”).

A sheet with the numbers can be printed/downloaded here.

Unit 5 Review

Articles and Adjective Endings

See summary tables at the end of the section above on adjective endings.

The Definite Article: Accented and Unaccented

The accented definite article serves as a demonstrative determiner or pronoun. Sometimes the word אָט is added for emphasis. For example:

The unaccented definite article may be contracted in the following cases:

The unaccented definite article may be omitted in the following case:

The accented definite article is never contracted or omitted.

The General Pronoun דאָס/דעם

The general pronoun דאָס/דעם refers to something (an object, objects, a situation, an action) without a grammatical connection to a specific noun. Sometimes it is demonstrative (and therefore accented) and sometimes not. For example:

More examples can be found in 5.4 נאָך פּרטים.

טאַטן, זײדן, מאַמען, באָבען

Nouns generally do not decline in Yiddish. In lesson 5.2 we learned a small group of exceptions – the words טאַטע/זײדע/מאַמע/באָבע. The forms in all cases are in the following table:

The Reflexive Pronoun זיך

The object pronoun זיך is reflexive, that is, it and the subject of the sentence refer to the same person or thing. It can be:

- the direct object:

- the indirect object:

- the object of a preposition:

The pronoun זיך is invariant: it does not change according to person, number, or case.

When a verb comes with זיך (always, or when it has a certain meaning), it is listed with זיך in a Yiddish dictionary. Such verbs are also listed with זיך in YiddishPOP vocabulary sections.

More information about זיך can be found in 6.5 נאָך פּרטים.

נישטאָ

The construction איז דאָ/זײַנען דאָ indicates existence or presence. When it is negated, the words נישט and דאָ merge:

דער אתרוג איז דאָ. ← דער אתרוג איז נישטאָ.

The negative article קײן comes with a nonspecific noun:

ס׳איז דאָ אַ מאַלפּע. ← ס׳איז נישטאָ קײן מאַלפּע.

עס זײַנען דאָ בענקלעך. ← עס זײַנען נישטאָ קײן בענקלעך.

The adverb דאָ (as opposed to דאָרט) never merges with the negative נישט:

דער אתרוג איז נישט דאָ, אין דער פּושקע. ער איז דאָרט, בײַ יאַנקלען.

See also 5.2 נאָך פּרטים.

The Past Tense

Helping Verb + Participle

A verb in the past tense has two parts – a helping verb and a participle:

- איך האָב געקאָכט.

- מאָבי איז געקומען.

The helping verb is האָבן or זײַן. The conjugated forms of each verb in the present tense are used.

The participle ends with ט– or ן–. It comes with the prefix –גע when the accent falls on the first syllable of the infinitive.

Further guidelines on the formation of participles can be found in 5.2 נאָך פּרטים together with lists of the helping verb and participle of all the verbs in YiddishPOP up to lesson 5.2. From lesson 5.3 on, the helping verb and participle of new verbs are included in the vocabulary movie. Lists of the helping verb and participle of all the verbs in YiddishPOP can be found in 6.5 נאָך פּרטים.

The participle of a verb with a converb is the same as the participle of the verb without the converb, but with the converb attached, for example:

- אַרױסגײן – אַרױסגעגאַנגען

- אַרײַנלײגן – אַרײַנגעלײגט

When two or more verbs in the past tense are coordinated with the same subject, only the first helping verb is required. This is the case even when some verbs come with האָבן and some with זײַן:

- איך האָב געקױפֿט די שאַל און (האָב) געגעבן צדקה.

- דאָס מײדל האָט אָנגעטאָן דעם מאַנטל, (איז) אַרױסגעלאָפֿן פֿון שטוב און (האָט) געכאַפּט דעם אױטאָבוס.

Word Order

On word order in past tense sentences, see below “word order in a declarative sentence without special emphasis”.

Directional Converbs: When the Base Form of the Verb is Absent

When a verb of movement comes with a directional converb (for example: אַרײַן, אַרױס, צוריק, אַרױף, אַראָפּ) and the type of motion is clear or unimportant, the base form of the verb is often omitted:

- פּינטל װיל אַרײַן װײַל ס׳איז קאַלט אין דרױסן.

- זיבן אַ זײגער בין איך אַרױס פֿון שטוב.

Omitting the base form of the verb is a matter of style. The sentences are also correct with it:

- פּינטל װיל אַרײַנגײן װײַל ס׳איז קאַלט אין דרױסן.

- זיבן אַ זײגער בין איך אַרױסגעגאַנגען פֿון שטוב.

Note:

See also 5.4 נאָך פּרטים.

(צו) + Infinitive

In 5.1 נאָך פּרטים we listed the cases where the particle צו precedes the infinitive. In the following table, the categories “verbs that come with an infinitive with צו and without צו” are expanded to include new vocabulary words from lessons 5.2 to 5.5. A second expanded version can be found in 6.5 נאָך פּרטים that includes the new vocabulary from unit 6.

When the infinitive includes a converb, צו comes between the converb and the verbal stem and all three are written as one word. For example:

- ביסט גרײט אַרױסצוגײן אין דרױסן?

- נעמי האָט פֿאַרגעסן אַרײַנצולײגן איר העפֿט אין רוקזאַק.

The Position Verbs לײגן, ליגן, זעצן, זיצן, שטעלן, שטײן

The six principle verbs that indicate position are shown in the following table in the infinitive and in the past tense:

The three verbs in the category “bringing into position”:

- come with the reflexive pronoun זיך when referring to something or someone moving on their own.

- often come with converbs that make the verb perfective, and frequently add information about the direction or goal of the movement.

Example sentences with all six verbs and with various converbs, as well as an explanation of the perfective aspect, can be found in 5.4 נאָך פּרטים.

Word Order in a Declarative Sentence Without Special Emphasis

The following table shows the order of the sentence units in a declarative sentence without special emphasis. Most sentences do not include all eight positions, but the units in any particular sentence are usually in the order shown in the table. Example sentences, and more details about each position and about departures from the usual word order, can be found in 5.3 נאָך פּרטים.

The table is ordered from right to left in accordance with the presentation in 5.3.

The same word order applies:

- In questions, with the question word in the first position.

- In the imperative, where the first position is empty.

Word Order in Compound Sentences

A compound sentence consists of at least two sentences (clauses), often linked by one or more conjunctions. Each clause has its own word order according to the eight positions in the table above; the conjunction itself does not occupy one of the eight positions because it is a connector, not a sentence unit. For example:

- נעמי האָט געזאָגט מאָבין אַז זי האָט געהאַט אַ שלעכטן טאָג.

- נעמי קױפֿט די קלײנע שאַל װײַל זי װיל אױך געבן צדקה.

- נעמי שפּילט אין קױשבאָל װען ס׳איז שײן אין דרױסן.

The conjunctions that we have learned so far in YiddishPOP are:

און, אָדער, אָבער, אַז, װײַל, װען

An indirect question is a compound sentence where the question word functions as a conjunction. For example:

- איך װײס נישט װען ער קומט.

- זאָג מיר װאָס ער טוט.

More about the conjunction אַז and about indirect questions can be found in 5.3 נאָך פּרטים.

More about word order in compound sentences is taught in lesson 6.1.